Rating: 4.8/5

A note: This review was first published on Down to Earth magazine’s website. Posting it here with their permission. They are doing important work in the areas of environment, climate change, and livelihood challenges faced by the global poor. Do check out their website and subscribe to their magazine if you can!

I was gifted this book at a time in my life when academic or journalistic works produced by my caste-class peers were tiring me out. And if academia seemed obtuse, social media debates arranged around SEO-friendly keywords simply looked out of touch. Writing and reading about politics, as a whole, was feeling somewhat like a chore. And that’s why I put off reading Mobile Girls Koottam for the longest time.

And I was wrong.

Whatever I may have expected this book to be, I never thought it would be fun. Flying through these pages, I learned to laugh at their inside jokes and rolled my eyes with them at the various inconveniences they have to handle every day. I felt my eyes stinging when they spoke of work and family troubles. I vehemently disagreed with some of them and passionately agreed with others – you know, as friends do.

That’s how it felt, like having friends.

Declaring friendship with these young women would be a loaded claim, coming from me. I belong to a very different socio-economic location after all. My struggles as a working woman have always been offset by a considerably large safety net. Nor have I faced most of the social constraints they have had to operate under.

And yet Satya, Kalpana, Pooja, Lakshmi, Abhinaya – and Madhu and Sam along with them – seemed to take my hand, gently seat me between them, pour me a cup of tea, and treat me to a slice of their very hectic day.

Rough Edges and Bitter Fruits

Was this experience colored by my own sense of alienation? Possibly, yes. But this is also the result of a consciously and conscientiously chosen narrative style that Madhumita Dutta – the scholar-activist who is the reader’s entry point into their shared space at ‘Muthu’s room’ – adopts.

Mobile Girls Koottam was born as a podcast – or ‘radio show’ as it is described in the conversations – created over six months by women workers of a locked-down Nokia phone factory. These podcasts have been translated from the original Tamil and edited for clarity. Each chapter represents one podcast episode, with a different topic of the day. In her foreword, Madhumita speaks about the painstakingly difficult task of editing these translations for clarity while maintaining the natural cadence of the conversations. As a result, this book reads exactly like a conversation – with pauses, non-topical banter, unfinished sentences, and the inevitable ellipsis when one loses a trail of thought.

And that’s where the charm of this book lies. It forces the reader to let go of their complacency of looking at these sessions from a separate, sanitized space and throws them right in the middle of these messy lives. It forces you to bite into the bitter fruit instead of juicing and sweetening it up for your convenience.

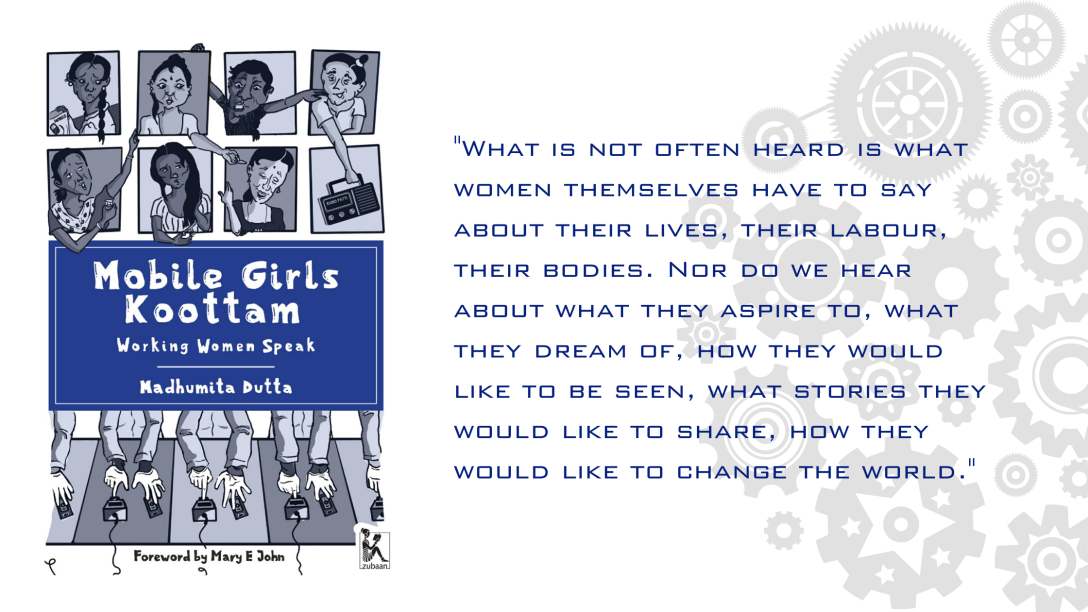

This is a conscious and political choice. Madhumita speaks eloquently about how these women are so often seen as a part of the invisible labouring masses, lumped together as victims – either of patriarchy or capitalism. “What is not often heard is what women themselves have to say,” Madhumita reminds us, “about their lives, their labour, their bodies.” As the English-speaking reader navigates the aforementioned ‘rough edges of the narrative, they are forced to pay heed to the actual voices of Satya, Kalpana, Pooja, Lakshmi, and Abhinaya.

The Researcher and the Subject

This narrative strategy is also the crux of Madhumita’s methodological politics. It would have been easy for her to write a standard non-fiction book that illustrates her ideas and impressions born of this experience and uses snippets of these conversations as examples.

It would have been the safer choice also, for there are many ideas expressed here that she probably won’t be comfortable with as an urban, middle-class, and for want of better words, ideologically progressive woman. She could have cradled these instances with her commentary and added as many caveats as she wished. It would have been far easier on the palette of her urban readers. That’s how most ethnographic research work reads.

Instead, Madhumita chooses to eliminate the authority of her position as the researcher. The researcher is on the same plane as the subject, and the unequal power dynamic between the two parties is subverted at every point. Even when she disagrees with them, Madhumita seldom fails to listen, adapt, and learn. And that is the underlying philosophy that allows Mobile Girls Koottam to bloom in a cacophony of several voices and resist attempts to reduce these women to any homogenized representation of working womanhood.

What Women Speak of

These are all women who have come to work in the factory from different caste and class backgrounds, have been subjected to different sets of rules and regulations in their homes, and are navigating life in the city and the factory with different levels of ease/hardship. They have varying ideas about society and selfhood and are robust in their agreements and disagreements.

They speak of dreams and hopes, past and future. They speak of opening a Chai shop for women only. You frown because gender segregation in supposedly equal urban spaces is frowned upon now. Then you realize what they are really talking about is the idea of a safe space, based on trust, lack of judgment and violence, and shame.

They speak of their girlhood, the customs around menstruation they had gone through, and what these customs meant to them. They speak of clashes with parents and siblings, of freedom and unfreedom, and of course, home– to escape from, to yearn for. They speak of the way they view themselves differently in the village and the city, and in turn, how the village and the city look at them. They speak of work and rest, joy and drudgery.

As their conversations unravel I slowly began to realize certain nuances, perhaps for the first time. For example, how even a workplace with ‘good’ labour practices can have complex and multiple layers of oppression woven into its very structure. How the narrative of personal growth is inherently class and caste-blind, as the requirements of daily factory work leave them almost no time or energy for expanding their skillset. That, maybe the difference between skilled and unskilled labour is just the accident of birth. Through these conversations, I learned how solidarities and safe spaces are forged in real time through considerable differences.

The delightful illustrations peppering this book deserve their separate paragraph. Madhushree’s work deliberately walks away from the polish and ‘prettiness’ of cookie-cutter software illustrations ubiquitous in publishing today. The bodies are hand-drawn, somewhat crudely, sparkling with joy, and chock full of personality. Madhushree’s women are not pretty, because they don’t need to be. They speak with their entire presence; and through each curve and whorl of pencil on paper, the joy, wit, anger, contempt, and mischievousness of these women are laid bare. Again, so refreshing and exciting, especially if you are looking at them after years of commercial publication exposure.

If you want to learn more deeply about the complex issues facing Indian workers in contemporary times, Mobile Girls Koottam: Working Women Speak is a wonderfully satisfying way to go about it. And if you are, like me, feeling a little cynical about politics lately, this book might be just the right dose of magic to push you out of the rut.